Welcome to the first blog post outlining critical social justice issues.

Every month (or so), you will find a short introductory paragraph and resources on a few social justice issues.

In this month’s post, we will begin by looking at the asylum system adopted by the Australian government and the cases of Ismail and Mehdi, refugees who have been detained for almost a decade. We will then move onto the ongoing Nakba (catastrophe) that has been occurring in Palestine since the 1940s. Finally, we will end with an evidenced argument that the care-to-prison pipeline in England and Wales is overrepresented by Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) children.

1. Australia’s Cruel Asylum System

Australia is known for it’s harsh, inhumane asylum system, including transferring people seeking asylum in Australia to offshore processing centres in Papua New Guinea and Nauru (Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law, 2021). They are detained in the processing centres, contrary to international law in most circumstances. Asylum seekers, including families with children, have been forced to live in poor conditions and suffer abuse (Human Rights Watch, 2015). The Australian government will not resettle anyone, even refugees (again, contrary to international law), in Australia, leaving those detained in a state of limbo (Refugee Council of Australia, 2022).

In 2013, Ismail Hussain arrived on Australian territory and was taken to an offshore processing centre on Manu Island (Paul Gregoire, 2020). He was detained there until late 2019, when he was transferred to mainland Australia, first to the Mantra Hotel and then to the Park Hotel in Melbourne (Paul Gregoire, 2020; Zoe Osborne, 2022). Also detained in Park Hotel is 24 year old Mehdi. As a child asylum seeker, Mehdi arrived in Australia at 15 years old and has been detained in the hotel ever since (Karl Mathiesen, 2022). There are 31 others detained in the hotel and thousands more throughout mainland Australia (Karl Mathiesen, 2022; Refugee Council of Australia, 2022).

The Park Hotel saw Serbian tennis player, Djokovic, detained for a few days whilst waiting for a decision regarding his deportation, after the government revoked his visa twice for failure to comply with covid-19 vaccination requirements. Djokovic was able to return safely to his home in Serbia, whilst Mehdi and Ismail remain.

“We are locked up in a room. I can say 24 hours a day. 24 hours a day [in] a room… You can see through the window. People moving on with their lives… and it’s torture to us. Torture to us… You know, all we want is the same thing that normal people do. But without reason it has been taken away for nine years.”

Ismail Hussain (Zoe Osborne, Al Jazeera, 2022)

Written Resources

Offshore Processing: An Overview, Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law, 2021

Australia: 8 Years of Abusive Offshore Asylum Processing, Human Rights Watch, 2021

Novak Djokovic leaves behind Australia’s ‘white torture’, Karl Mathiesen, 2022

Park Hotel detainees housed alongside Novak Djokovic describe ‘disgusting’ and ‘cruel’ conditions, Tracey Shelton, 2022

Videos

Djokovic is gone, but refugee Mehdi continues to wait for freedom, The Age, 2022

2. Occupied Palestine

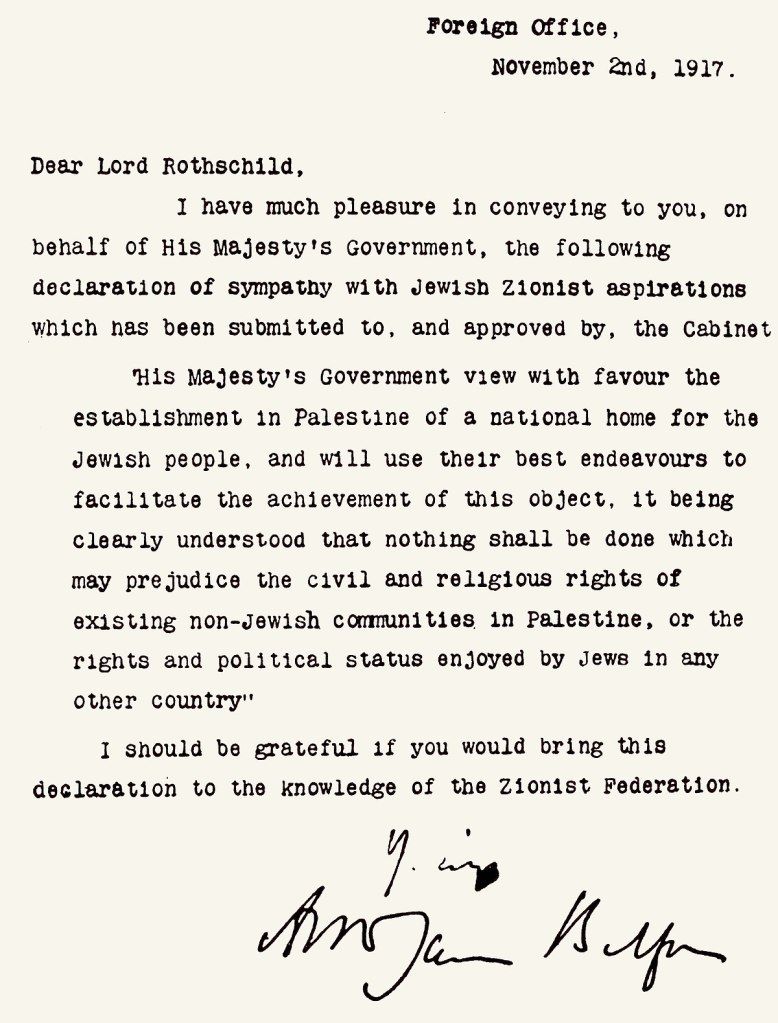

Since the late 1940s, Palestine has been occupied by Zionist colonial settlers. Plans to do this predates the 1940s. In 1917, the Balfour Declaration was drawn up by Britain’s Foreign Secretary, Arthur James Balfour, and sent to a leader of the Zionist movement, Baron Rothschild (Rawan Damen).

If you would like a more detailed account of the history of the occupation of Palestine, read “Al Nakba” by Rawan Damen.

In 1948 two thirds of the Palestinian population were ethnically cleansed in the Nakba (Palestine Solidarity Campaign). The ethnic cleansing continues today, with Palestinians being forcibly removed from their homes, which are often demolished, in neighbourhoods such as Sheikh Jarrah in East Jerusalem and the al-Araqib village in the Naqab (Palestine Solidarity Campaign). The forced, violent, removal of Palestinians from their homes has created over 5 million refugees as of 2019 (Amnesty International, 2019).

Written Resources

Information about Palestine, Palestine Solidarity Campaign

Factsheets, Palestine Solidarity Campaign

Videos

3. Care-to-Prison Pipleline

In England and Wales, Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) children are disproportionately represented in the youth justice system (The Lammy Review, 2017; HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 2017-18). There is also an increasing number of BAME children being taken into care (Department of Education, 2019). Offering an explanation for this increase are austerity measures resulting in increased child poverty, particularly amongst BAME children, as well as the decreased availability of broader children’s services due to reduced funding, resulting in an increase in demand for child protection services (Child Poverty Action Group, 2020; Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2020; The Association of Directors of Children’s Services Ltd, 2017; Child Poverty Action Group, 2020). Furthermore, BAME people are more likely to live in the most overall deprived 10% of neighbourhoods, where children are more likely to be in care (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, 2020; The Child and Welfare Inequalities Project, 2020). The argument that increasing numbers of BAME children being taken into care as a result of austerity measures is futher supported by the Department of Education in their 2018/19 report including a new category concerning reasons for being taken into care, this being ‘due to low income or socially unacceptable behaviour’ (Department of Education, 2019).

Looked after children (children looked after by a local authority for more than 24 hours) are reported to experience negative stigma, which can manifest as the perception that such children tend to exhibit negative behaviour (Darker, Ward and Caulfield, 2008, cited in Katie Hunter, 2019; Hunter, 2019). This stigma adversely affects looked after children when encountering the youth justice system (Coram Voice, 2015 cited in Hunter, 2019). It is consequently arguable that the stigma BAME looked after children experience is compounded by racism. Research carried out in 2016 by the Prison Reform Trust revealed that the number of BAME children who are currently (at the time the research was carried out) or had previously been looked after are overrepresented in the youth justice system. This demonstrates that the multifaceted inequalities resulting from the combination of being in the care system and racism places BAME looked after children at a heightened risk of being criminalised (Hunter, 2019). The care-to-prison pipeline is therefore more likely to be experienced by BAME children who are currently, or who previously have been, in the care of local authorities.

Thank you for reading the first post outlining and providing resources on some critical social justice issues. We will end with a quote by journalist, author and podcaster, Reni Eddo-Lodge:

The mess we are living in is a deliberate one. If it was created by people, it can be dismantled by people, and it can be rebuilt in a way that serves all, rather than a selfish, hoarding few.

Reni Eddo-Lodge, Why I’m No Longer Talking To White People About Race

Leave a comment